In the early part of 1649, the spanish painter Diego de Silva Velázquez received a commission from King Philip IV to travel to Italy. Among his other courtly functions as valet de chambre to the King, Velázquez was in charge of decorating the royal quarters. This would be the modern equivalent of having a luxury designer decorate the weekend cottage. Such are the privileges enjoyed by royalty.

Velázquez’s mission on this, his second trip to Italy, was to use his shrewd artistic judgment, backed with the royal purse, to acquire select paintings and sculptures that would later adorn the walls and rooms of the various royal palaces.

He had recently celebrated his 50th birthday, and he must have been going through that stage of life that today we associate with a midlife crisis, or rather, a late-life crisis, given the levels of life expectancy at the time. We can only imagine Velázquez’s excitement at the thought, not of the mission itself, but of the opportunities that a voyage of this nature presented. It would remove him from the stale environment of the Spanish court, plagued as it was with frustrated political expectations, and allow him to enjoy the revitalizing air of an Italy that was flourishing as the artistic epicenter of the time.

Once there, Velázquez spent his first few months scrutinizing the Italian art market and competing with representatives of other European monarchs. They were all on the lookout for artistic bargains. He made the most of his time in Italy by buying paintings — particularly works from the Venetian school as this was both his and Philip IV’s favorite. He also bought sculptures, even when they were only based on molds of classic works, and debated his preferences with other painters. Velázquez was an admirer of both Titian and Paolo Veronese, but he did not share the Italians’ blind devotion to Raphael.

The Pope Commission

As painter to the powerful Spanish royal court, Velázquez enjoyed a certain level of prestige, even in Italy, where artistic egos would compete against each other in order to win the biggest share of the backing provided by the nobility. Several months had passed since his arrival, and he had still not lifted a paintbrush, when Velázquez received word that Pope Innocent X wanted him to paint his portrait.

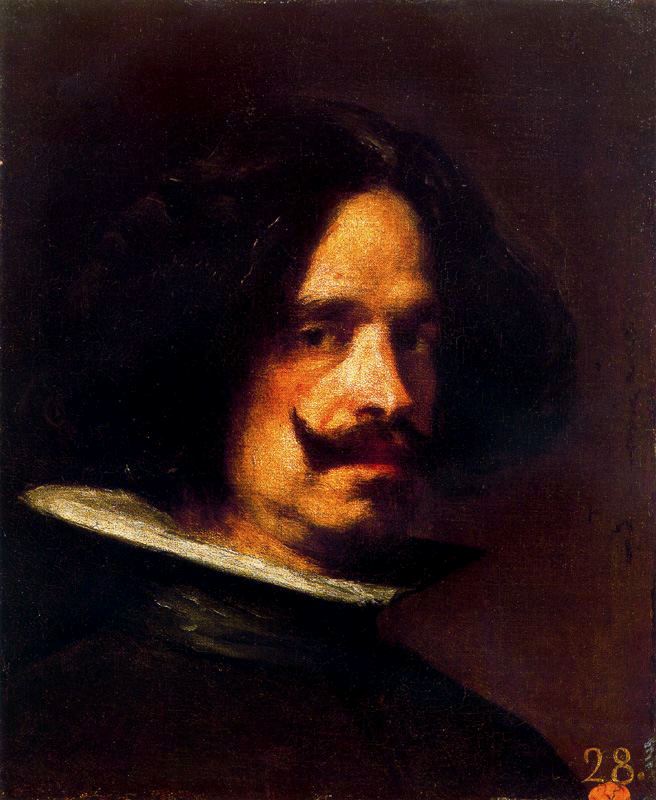

Juan de Pareja by Velazquez

Velázquez was keen to do so as he needed the support of the papal Curia for his longstanding ambition to join the noble knights of the Order of Santiago, and he hoped that the high quality of his work would win him the Pope’s backing. It was a risky assignment, however, and one that could jeopardize his prestige as a painter; everyone would have their eye on him, waiting to see the result of his efforts. A prudent man, he decided to do a practice portrait beforehand, and it was his Moorish servant, Juan de Pareja, who was made to pose for it. The end result was exceptional. Velázquez had already been accepted into the two most important art circles in Rome, the Accademia di San Luca and the Congregazione dei Virtuosi. This gave him the right to exhibit his works in the cloister of the Pantheon alongside those of his contemporaries and other, older, artists. As his biographer Palomino recounts, visitors could not help but admit that, while the other works were paintings, Velázquez’s was truth itself. And so, with his confidence suitably boosted, Velázquez got ready to paint the Pope’s portrait.

Troppo vero

Despite his 75 years, Innocent X kept himself vigorous and active. But he possessed a dark, distrustful personality and was, by all accounts, one of the ugliest men in Rome. Velázquez executed the portrait in his customary manner, i.e. with no prior drawings or sketches. It takes a great deal of confidence and a superb eye to capture a subject’s essence in the short amount of time that the Pope agreed to pose for him.

Innocent X by Velazquez

The pontiff was pleased with the result, but he could not refrain from exclaiming the famous phrase “Troppo Vero” — too real. His lack of good looks must have been significant because he felt sufficiently flattered by the portrait as to hang it in his papal office, despite Velázquez having immortalized him with a surly, suspicious expression.

The painting spent many years hidden from view in the rooms of the Pope’s family, the Doria-Pamphilj. When it finally came into public gaze, in the mid-19th century, it was greatly admired by all. For a long time it was an icon and point of reference for painters. This is especially true of the Russian school on account of the fact that a copy — made only of the bust and by Velázquez himself — ended up in St. Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum. Painters such as Brülove, Kramskoi, and Repin considered it sublime and beyond description. Kramskoi expressed his admiration for Velázquez’s work in 1876, saying:

“Anyone would be left discouraged by what that man could do. Compared to him, everything else is superficial, inexpressive and insignificant…Dear God, I know so many wonderful works. And how many painters have there been who, with only half the qualities he possessed, have deserved their very sound reputations? But this is something absolutely extraordinary.”

Many others consider it to be the greatest portrait of all time. Today, it shares a small space in Rome’s Doria-Pamphilj Gallery with a bust of Pope Innocent X by Bernini, another genius and also a contemporary of Velázquez.

Velázquez in love

During his time in Italy, Velázquez had a bit on the side with an Italian woman. History does not record her name, but confirmation appears to exist that as a result of this relationship he had an illegitimate son who was christened Antonio de Silva.

The Rokeby Venus by Velazquez

The most romantically inclined believe the woman to be the model who posed for Velázquez’s sublime painting The Rokeby Venus (also known as The Toilet of Venus). A great deal can be said about this wonderful painting. Suffice to say, despite no date being assigned to the work, he probably did paint the woman during his second trip to Italy. At the time, the intransigent Spanish inquisition was on the ball, and it is difficult to imagine Velázquez secretly painting the picture somewhere within the palace quarters.

It is therefore understandable that he was reluctant to return to Spain, where the drab Spanish court and a boring marriage awaited him. He used all sorts of excuses to delay his return as long as possible, while an increasingly impatient Philip IV sent him letters and ambassadors to complain of his nonchalant behavior and demand his return. Eventually, after two and a half years away from home, he was left with no option but to obey the King’s orders and return to Spain.

Velázquez’s undoubted brilliance existed alongside an otherwise restrained and unremarkable personality. He can be compared to Bach in that, when they removed their wigs and laid down their paintbrushes and musical scores, respectively, they became ordinary family men who displayed no eccentricities or outbursts of an exceptional nature.

Velázquez enjoyed outstanding social advancement for a painter, rising from his humble roots in Seville to become the Royal Chamberlain. And two years before he died, he achieved his long-held desire to become a knight of the Order of Santiago, despite opposition from the Order itself, who considered him an upstart and a commoner.

Velázquez’s second visit to Italy was his greatest journey, representing as it did a breath of fresh air for a man whose life, laden with convention, mediocrity and submission, was dedicated to serving the powerful. His free and cultured spirit was able to enjoy beauty and passionate love for the first time. Personal experiences do not normally pass into the history books, but Velázquez’s were surely the reason for his personal state of exultation, inspiring him to produce some of the greatest painting masterpieces of all time.